In this week’s New Haven Advocate, I’ve got an essay on Glenn Beck-as-author, disguised as a dispatch from his latest simulcast book event. Through his radio and television shows, Beck can deliver huge sales boosts to obscure political treatises and to mass-market thrillers — and this gets at what the publishing industry calls his “platform.” It’s why he sells books. But why does he write them? I come to a pretty cynical conclusion in my essay, but other explanations do exist. Still, Beck’s books don’t fit with his off-the-cuff nature. At the book event, he turned a Primanti Brothers sandwich, a Pittsburgh delicacy made up of beef, french fries, and cole slaw, into a metaphor for America’s budget crisis. This metaphor allowed Beck one of his few Obama attacks — he introduced the sandwich as “Michelle Obama’s worst nightmare” — but it also reveals how, um, adaptable he can be. It seems Beck didn’t call Primanti Brothers until six hours before the show. He ordered 300 sandwiches.

Category: Features

By Committee

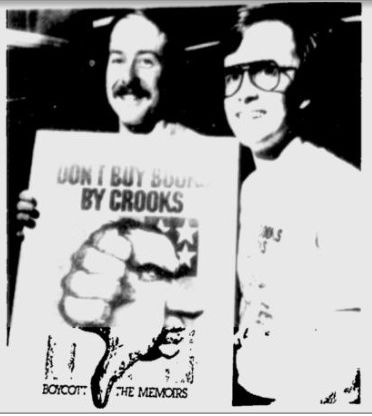

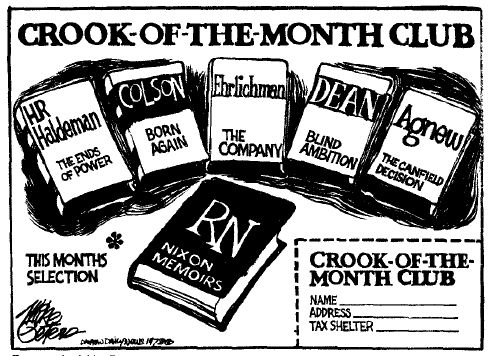

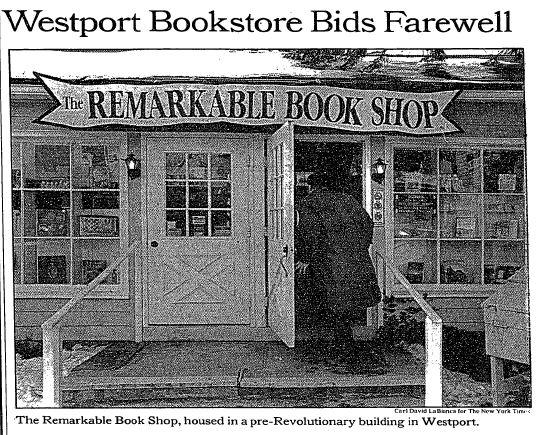

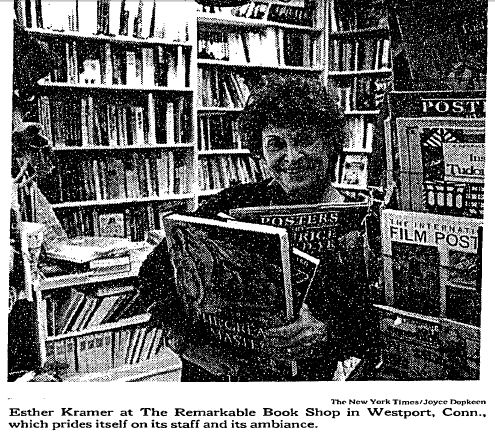

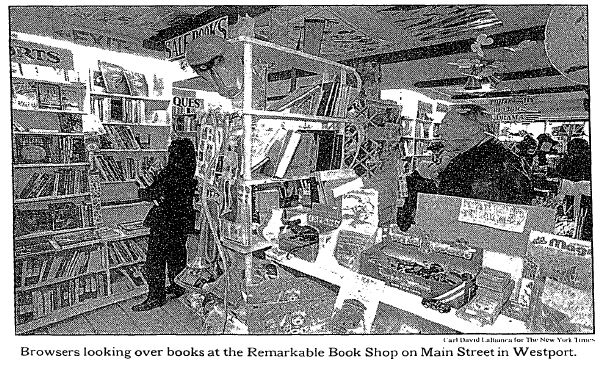

In this Sunday’s New York Times Book Review — and just in time for the release of George W. Bush’s memoirs — I’ve got an essay on the crazy (but long forgotten) protests surrounding the release of Richard Nixon’s memoirs. My cast of characters includes Tom Flanigan and Bill Boleyn (pictured above), the co-founders of the Committee to Boycott Nixon’s Memoirs, and Sid and Esther Kramer, the co-owners of Westport, CT”s Remarkable Book Shop (pictured below). Really, though, it includes just about everyone living in 1978 — because RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon came with a degree of media hype achieved by no presidential memoir before or (so far) since.

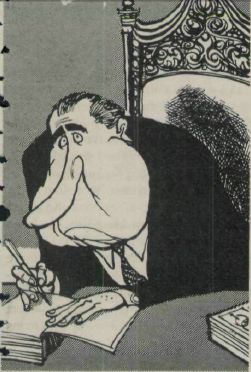

For further proof of this, check out this contemporary news broadcast (YouTube) and, below, some great caricatures of Nixon as author. I also wrote a blog post for the Times about the two “deluxe” editions of Nixon’s memoirs — this phenomenon of presidential publishing also occurred with Carter’s, Reagan’s, Clinton’s, and, now, Bush’s books — and there are some images of those editions. After that, as promised, a few old newspaper photos of the Remarkable Book Shop. Sid told me that, when the RBS closed in 1993, Paul Newman called him and said, “Don’t close — you can’t close.”

The New Republic (1974)

The New Republic (1978)

Boston Globe (1978)

* * *

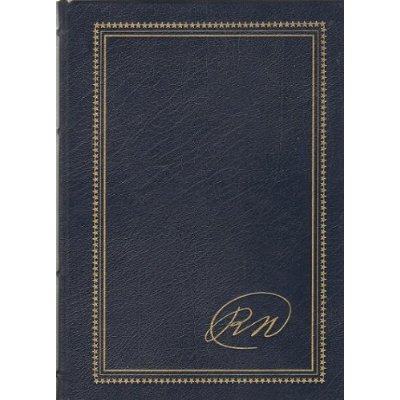

RN‘s $50 “deluxe” edition, with slip case

RN‘s $250 “numbered presentation” (and

RN‘s $250 “numbered presentation” (and

leather-bound and gold-detailed) edition

The “numbered presentation”

The “numbered presentation”

edition’s certificate of authenticity

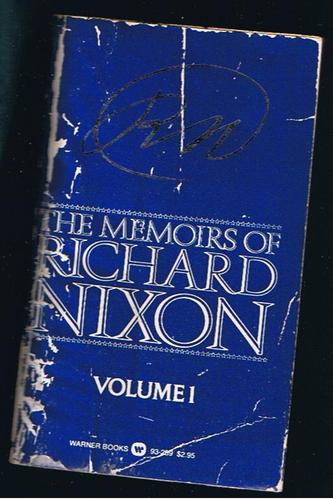

The first volume of Warner’s paperback edition ($2.95)

The first volume of Warner’s paperback edition ($2.95)

* * *

The RBS in the 1960s (Dan Woog)

New York Times (1994)

New York Times (1987)

New York Times (1994)

A Profile of Jill Lepore

In this week’s “Ideas” section of the Boston Globe, I’ve a profile of Jill Lepore and her new book The Whites of Their Eyes: The Tea Party’s Revolution and the Battle over American History. Lepore was a great interview. (A couple of favorite [and context-free] lines: “I drink my cup of coffee and I think about the history of coffee. In my brain, everything unfolds on a time line”; “Arthur Schlesinger didn’t have to deal with email.”)

Lepore’s also written an interesting, if uneven, book. One thing I couldn’t get to in my profile was her critics within the academy. Lepore’s smartest move in The Whites of Their Eyes may be accusing the Tea Party of presentism — the Bicentennial was also, in Lepore’s phrase, “a carnival of presentism” — because this makes it harder to level one of history’s dirtier words at her. (The president of the American Historical Association defines presentism as “the tendency to interpret the past in presentist terms.”) Still, that’s exactly what people have done to her previous work. Consider the end of Brendan McConville’s blistering review-essay of Lepore’s New York Burning:

The unintended lesson within New York Burning is for those of us who study early America, and it goes something like this: colonial Americans aren’t like us, and that is what is truly disturbing and fascinating about them. Efforts to make their lives a long prologue to the emergence of our own world don’t work, even though some things they did clearly affect us.

I will say that, when it comes to writing about complex historical ideas for popular audiences, I’ve developed a lot of sympathy for Lepore. In the profile, for example, I wanted to explain why Sharron Angle was crazy to call Jefferson and Franklin “social conservatives.” Jefferson was easy enough — as was Franklin, if I’d talked about his views on gender inequality. But I figured I had to broach the issue of slavery at some point in a story on colonial America, so I went with Franklin’s abolitionism. Problem is, I’ve read David Waldstreicher’s excellent Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution, a book that shows this matter is much more complicated than simply referencing Franklin’s run as president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. I had to finesse the point, and quickly. I’m embarrassed to say one draft had “Franklin’s semi-abolitionism,” which my editor smartly shot down. “Franklin’s public abolitionism” might not be much better, but I hope it at least registers the skepticism conveyed in Waldstreicher’s book. It’s a small example, but one that nicely illustrates the difficulties in practicing responsible public history.

One more thing: it’s worth rewatching Santelli’s original “rant heard round the world,” if only for the studio’s confused reactions. “It’s like mob rule there” and “he’s a rabble-rouser” — no surprises there, but how about this line: “Rick, I congratulate you on your new incarnation as a Revolutionary leader.”

Brace yourself: the latest, greatest edition of Mark Twain’s Autobiography is almost here

[Slate]

At Slate, I’ve got an essay on the crazy behind-the-scenes history of Mark Twain’s Autobiography and its various editions. The latest one just arrived, and, over the last six months, it’s been getting some unbelievable hype, thanks in large part to Twain’s instructions that it not be published until 100 years after his death. But I try to show that this story is now repeating itself for the fourth time — and that there’s not that much new in Twain’s new book. Twain clearly overestimated the scandalousness of his autobiography. (Van Wyck Brooks gets the best line on this: “He is going to have a spree, a debauch of absolutely reckless confession. He is going to tell things about himself, he is going to use all the bold, bad words that used to shock his wife.”) But what if he always intended the embargo as more of a marketing stunt than anything else? That’s the question I kept in mind while researching and writing my essay. And if this is what Twain intended, it worked better than even he could have hoped.

One thing I couldn’t get to in the essay was my problems with the new edition of Twain’s autobiography, which is coming out from the Mark Twain Project and the University of California Press. (What follows is of such limited appeal that I’m going to assume you know who Paine, DeVoto, and Neider are.) The new edition promises to be a major scholarly event, but it’s being treated like more of a popular or literary one. And the editors at the Twain Project have gleefully nodded along with the media’s embargo-driven excitement. (Well, they did push back on the vibrator.) In July, the Twain Project supplied the New York Times with “some of Twain’s spicier comments” for the newspaper’s front-page story on the new edition. But those comments were all published back in Paine’s edition! The attack on Theodore Roosevelt appears, in full, in Paine. So does the comment on Thanksgiving Day (though Paine fussily [and typically] swapped Twain’s “consequently” for “hence”). And while Paine did hold back some of the nastier flourishes in the third example, he still included Twain’s riff that Christianity “is now nothing but a shell, a sham, a hypocrisy.”

Here’s what the Times‘ reporter concluded:

In his unexpurgated autobiography, whose first volume is about to be published a century after his death, a very different Twain emerges, more pointedly political and willing to play the role of the angry prophet.

This simply isn’t true. That Twain emerged a long time ago; whether or not we’ve noticed is a different matter. I don’t fault the Times‘ reporter for this, just like I don’t fault Granta for hyping its “exclusive first excerpt” of Twain’s autobiography, an excerpt that appeared in full in both Paine and Neider’s editions. But I do fault the Twain Project. Again, as scholars, the editors at the Twain Project have done incredible work. They’re going to put the full autobiography (and its enormous number of variants) online for free. They’ve devoted 300 of the new volume’s 700 pages to a terrific textual apparatus. But these scholarly bells and whistles just make the Twain Project’s complicity with the hype that much more disappointing.

It also makes their treatment of Neider and DeVoto unconscionable. DeVoto represented an enormous improvement over Paine, opening the Twain Papers up to other scholars for the first time. (I’ve developed a bit of a scholarly crush on DeVoto and will, at some point, try to write another post on him and Twain.) But Neider and DeVoto show up in the new edition of Twain’s autobiography only to get knocked down. In what passes for an insult in scholarly circles, the editors at the Twain Project note that DeVoto modernized Twain’s punctuation “with great satisfaction.” There’s little mention of Clara’s crushing influence — which was, if anything, worse than what comes across in my Slate story. DeVoto and Neider were passionate, hard-working, underpaid scholar-critics who introduced Twain’s autobiography to several generations of readers. It’s a mistake to slight either their efforts or the impossible conditions under which they labored. In fact, even more than aiding and abetting the embargo-driven hype, it is a form of scholarly malpractice.

The surprising fate of David Markson’s library (which wasn’t actually that surprising)

This Sunday, in the Boston Globe‘s “Ideas” section, I’ve got a story on the fate of authors’ personal libraries — the books they owned, annotated, and probably threw against the wall in frustration. One of my story’s main points is that these libraries get far fewer resources than they should, and a corollary to this is that they get far less media attention, too. (I suspect the reason, in both cases, stems from our cultural obsession with The Author, alone and inspired: it’s why we save Norman Mailer’s ceremonial key to the city of Miami, but not his books.) Still, if you want to learn more about this subject, I’d recommend this Harper’s essay on Updike’s books (along with this slideshow); this New Yorker story on the Harry Ransom Center; the Ransom Center’s own info on David Foster Wallace’s books; and this Atlantic essay on Hitler’s library.

My story touches on tons of iconic authors — Wallace, Updike, Mailer, Don DeLillo, William Gaddis, Ernest Hemingway, Stephen Crane, Mark Twain, Herman Melville — but it starts with a cult one: David Markson. A few weeks ago, Markson’s library was anonymously scattered throughout The Strand, New York’s biggest independent bookstore, and Markson’s devoted fans have been trying to put it back together digitally. (See here and here for examples.) I’ll include some insidery stuff on Markson at the end of this post, but first I want to tell the full story behind Melville’s library. I didn’t have the space to do this in the Globe, but its fate is fascinating and complicated and even affecting. What’s true of Melville’s books is true of each author mentioned in my story, plus a whole lot more besides.

Melville died in 1891, a frustrated and largely forgotten writer. His estate inventory noted some “personal books numbering about 1,000 volumes” and priced them at $600. Melville’s widow, Elizabeth, kept a few and sold the rest to New York City book dealers. (She never made a list of the books, and Merton Sealts, whose Melville’s Reading is my source for much of this, could establish only 390 of the books Melville owned.) One of Melville’s granddaughters would later recall that, when it came time to winnow down his library, Elizabeth and the rest of the family decided to save the smallest books so they could save more of them. Some family members ended up willing their copies of Melville’s books to Harvard’s Houghton Library, others to the New York Public Library.

If the whole thing sounds frustratingly slapdash, that’s because it was. In the first edition of Melville’s Reading, Sealts lamented that, while Melville clearly knew Plato and Milton, “no one has located his set of Plato or copy of Paradise Lost.” This statement is no longer true — once the Melville revival kicked in, more books started popping up and getting auctioned for obscene amounts — but it still gets at the problems with how we handle the libraries of contemporary authors, at least for as long as they remain contemporary.

And yet Melville’s books did matter to his family. One of the titles Elizabeth kept — and one of the titles that survived — is Isaac Disraeli’s The Literary Character. There, in 1895, four years after her husband’s death, Elizabeth marked and initialed the following quotation from another author’s wife:

My ideas of my husband . . . are so much associated with his books, that to part with them would be as it were breaking some of the last ties which still connect me with so beloved an object. The being in the midst of books he has been accustomed to read, and which contain his marks and notes, will still give him a sort of existence with me.

This calls to mind another marked passage, this one from David Markson’s copy of The Shorter Novels of Herman Melville. In fact, it’s the only passage Markson marked in the book’s 50-page biographical introduction:

[Melville] challenged the world with his genius, and the world defeated him by ignoring the challenge and starving him. He stopped writing because he had failed and because he had no choice but to accept the world’s terms: there is no mystery here. This was not insanity, but common sense.

* * *

So, back to Markson. When John Updike got rid of some books, the Boston Globe broke the news — the headline: “With little fanfare, Updike bids books adieu” — and an AP story about it snaked around the country. When David Markson got rid of some books, he mentioned it in an interview with Bookslut — and not even his fans noticed. “I’ve sold off quite a few in the last ten years or so, just for breathing space,” Markson said. “And in all honesty, I’ve been very tempted lately to dump the whole lot of them.” The interviewer asked Markson if the books were worth any money. “No, virtually none,” he replied. “If you look closely you’ll see that they’re all worn and faded — well, I’ve never kept dust jackets — plus, they’re written-in and whatnot. A lot of the spines are even so tattered that they’re scotch-taped to hold them on.”

While Markson brought this up in other late interviews, no one thought to mention it in the uproar over his library’s dispersal at The Strand. As I detail in the Boston Globe, though, that’s clearly what Markson wanted for his books. Johanna Markson, his daughter, told me that sending his books to The Strand “was the one thing we could do for him — he would never let us do anything else.” (Johanna later corrected herself: Markson would ask her to find and print things off the Internet when the New York Public Library’s Reference Desk couldn’t locate what he needed.) Elaine Markson, David’s ex-wife and literary agent, told me that “he had an intensely close relationship with The Strand over the years — they were fabulous to him, and he wanted to do something for them.”

Elaine added that she and her children “were impressed by the outpouring online — we didn’t know. I don’t know that David did.” Fred Bass, The Strand’s owner, also seemed surprised. “To be frank with you, after all the media coverage I wish I had kept his books together,” Bass said. “But I didn’t realize the scope of it until I was nearly through with it, and by that time it was too late.” (Elaine said there will be a memorial service on October 7 at New York University, even though Markson didn’t want one; you can find more info here.)

Markson’s New York Times obituary stressed that he was both “a novelist well known largely to other novelists” and “a central figure in the Village writing scene.” As I reported this story, Markson’s personal connections kept coming up. Tom Staley, the director of the Ransom Center, remembered meeting Markson in New York long ago: “I met him as a kid, had a drink with him and Dylan Thomas.” Ralph Sipper, a book dealer and longtime friend of Markson’s, helped him sell his literary correspondence to make ends meet. There’s more on this in the Globe story, and another book dealer I quote there, John Wronoski, told me that, after reading Markson’s books, “for the first and only time I wrote a writer a note of appreciation.” A few years later, Wronoski helped Markson go through his papers and identify things that might be worth selling. “It wasn’t a large archive,” Wronoski recalls. “He didn’t have multiple drafts, and he wasn’t the kind of writer who developed lots and lots of ideas and then killed some of them. He had a clear idea of what he wanted to write, and then he wrote it.”

A few private individuals and some university libraries do have small Markson holdings. The University of British Columbia has some Markson letters relating to Malcolm Lowry. (Here’s the finding aid, a .pdf.) The University of Delaware has some of Markson’s letters to Gilbert Sorrentino. Stanford University has some other Markson / Sorrentino letters and — even better — some Markson items in its extensive Dalkey Archive / Review of Contemporary Fiction collection. This latter material includes multiple typescripts of Wittgenstein’s Mistress, starting with an early draft titled Keeper of the Ghost. A Stanford librarian told me that the typescripts are not heavily annotated, but do come with some letters between Markson and his Dalkey Archive editor, Steven Moore.

You’ll notice that, in each of these instances, the Markson materials supplement the library’s preexisting collection. In other words, Markson is never the main draw. Increasingly, most libraries must focus their collecting — geographically, thematically, whatever — and Markson simply didn’t possess the star power to overcome these restrictions. As I mention at the end of the Globe story, the only real shot for a “David Markson papers” will come at a smaller library like Ohio State’s. Geoffrey Smith, head of Ohio State’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Library, told me that “the Ransom Center can go out and get established writers, but we have always had to scout out and predict. We want those writers we think will be studied in 100 years.” (To get a sense of the field’s rise, see this Matthew Bruccoli essay, in which he describes arriving at Ohio State in 1961 and finding that its rare books room consisted of 100 titles and a “locked janitor’s closet.”)

The Ransom Center, which inaugurated our current archival arms race, keeps an internal list ranking around 600 living writers, a list it uses to determine its next targets. When I asked Staley about Markson’s place on this list, he diplomatically said that Markson was “on our list, but didn’t rise to the top.” I understand the frustration at Markson’s library being dispersed. But I also find it oddly inspiring that he was able to leverage the current literary economy in such a way that he could continue writing up to his death. Because Markson’s last books were his best.